The Helicopter Savant

Augusto Cicaré’s rotorcraft finally take off.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/df/7edf1f07-21c3-41c8-8770-57153e73a067/24e_jj2017_svh4_live.jpg)

At the world’s largest helicopter trade show—the annual Heli-Expo, held in Dallas last March—there were signs that the worldwide commercial helicopter market was finally beginning to recover from the recession. Amid the tentative good news was great news for Augusto Cicaré. For the first time at the show, the diminutive 80-year-old Argentinian showed off his helicopter company and a revolutionary new trainer.

Cicaré is a rotorcraft savant. By the time he was 11, he was working a metal lathe and fabricating parts to assemble engines. A year later he left school and built motorcycle engines to earn money to buy helicopter parts. At age 20, he was flying his first homebuilt helicopter, the ultralight CH-1. He didn’t have a pilot’s license. At the Expo, he recalled: “I had never even seen a helicopter fly before. I was so nervous my knees were shaking.”

Cicaré’s work soon came to the attention of the Argentine air force. “They heard some crazy man was building a helicopter in his backyard, so they came to see me,” he says. The government periodically funded Cicaré’s design work over the next 30 years, but he never got consistent support beyond the prototype stage. To keep his projects funded, he started building race car engines—for Formula One racers and others—and gained international acclaim for his designs.

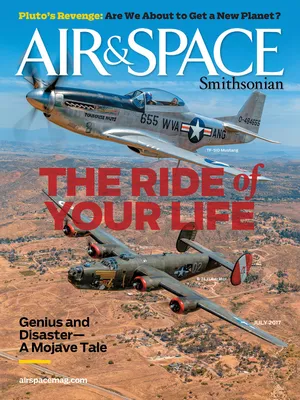

For most of its history, Cicaré’s helicopter business consisted of three people: Cicaré, his brother, and a neighbor who worked with sheet metal. Few in this country had heard of the company until four years ago, when China’s DEA General Aviation (DEAGA) saw the potential in a helicopter trainer Cicaré had designed. The SVH-4 is a single- or double-seat helicopter attached to a movable platform by an adjustable tether, which allows student pilots to practice lifting off and hovering at three feet or less. The SVH-4 can’t be rolled, and since it doesn’t need to be insured or serviced like an actual flight helicopter, it costs little to operate.

Up to 10 hours in the SVH-4 can be used toward the 40 hours needed for a helicopter pilot’s license. Michael Killian, who runs U.S. operations for DEAGA, says the company has even been approached by a Las Vegas company that thinks tourists will enjoy taking “flight” in one. In 57 years of business, Cicaré has sold approximately 60 helicopters, and nearly all of those sales have been in the last three years.

Cicaré, however, was a legend long before his business finally made it. The swarms of people who approached him at the Heli-Expo often knew his whole life story but were surprised to discover he ran a factory to sell his unique designs.

According to Raúl Oreste, the commercial strategist for Cicaré Helicopters, the reception the company got at the Heli-Expo “gave Augusto so much energy and ideas for future projects. He got back to the factory so pumped that we are having a hard time keeping up.”

Cicaré can even fly now—officially. A few years ago an Argentinian air force officer inquired about Cicaré’s pilot’s license. The inventor admitted that he “never had the money or time” to get one, and worried the jig was finally up. The officer had other ideas. “You obviously know how to fly,” he said, and arranged for Cicaré to—at least according to a piece of paper—finally become a pilot.