A London exhibition takes the history of textiles out of the shadows

Today, the art world takes textiles seriously. Thanks to pioneers such as Anni Albers, Judy Chicago, Alighiero Boetti and Faith Ringgold, we’re accustomed to seeing cloth in art museums almost as often as canvas. Yet the history of textile practices remains in the shadows.

Thanks, then, to the Bulldog Trust, a philanthropic organisation whose neo-Gothic showcase, Two Temple Place on London’s Embankment, is currently home to an exhibition devoted to seven women who collected textiles before they were in vogue. Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles centres on the collections, research and scholarship of Edith Durham (1863-1944), Louisa Pesel (1870-1947), Olive Matthews (1887-1979), Muriel Rose (1897-1986), Enid Marx (1902-98), Jennifer Harris (b. 1949) and Nima Poovaya-Smith (b. 1953).

Not only does it introduce us to a world hidden from all but connoisseurs, it also testifies to the geopolitics of cloth. Most of these collections took root not in London but places such as Manchester and Bradford, where the textile industry flourished and both practitioners and inspiration came from across the world — particularly south Asia.

The show’s main gallery opens with the collections of Durham and Pesel, both of whom were pioneers in recognising the artistic and sociopolitical worth of textiles. Durham, the daughter of a surgeon, set off for the Balkans in 1900 in order to recuperate from the strain of caring for her mother. Returning often over the next two decades, she eschewed those who “stayed for a fortnight at the Grand Hotel and never made it up country”. Instead, she rode through the hills on horseback, making notes, drawing, photographing and collecting samples of textiles and jewellery.

Durham also immersed herself in the region’s volatile politics, nursing the wounded during various conflicts including the Balkan Wars (1912-13), and reporting for British newspapers. She became a passionate supporter of the Albanian cause and came in for criticism, including by the British intellectual and novelist Rebecca West, for her anti-Serb sentiments.

In London, we see a clutch of beautiful pieces — all of which Durham donated to the Bankfield Museum in Halifax — including a gorgeous sleeveless waistcoat, known as a “jelek” in Albanian, which is braided elaborately in gold by male embroiderers. Also present are Durham’s own shoes (“opanke”) woven from twine and hide and soaked in oil to “mould themselves to the feet”.

Pesel was also a traveller. Originally from Bradford, she studied textile design at the Royal College of Art before taking up a post as director of the Royal Hellenic School of Needlework and Laces in Athens. Regarding the fabric designers of Turkey and Greece as “masters of colour”, she assembled a collection of textiles from those regions, and elsewhere in Europe.

For Pesel, textiles were as much teaching aids as artworks. On show here, a fragment of what is thought to be the hem of a Greek skirt, embroidered in rich claret silk in a Cretan feather and stem design, is typical of samples she liked to see “flipped back and forth” so her students could understand structure and technique first-hand.

After the first world war, Pesel went on to teach embroidery to refugees, shell-shocked soldiers and the wives of unemployed men in the 1920s — a scenario illustrative of Britain’s postwar trauma. Also symptomatic was male resentment at British women since they won the right to vote in 1918. The bitterness damaged female employment prospects and made self-employment an attractive option for entrepreneurial women such as Muriel Rose.

In 1928, Rose opened The Little Gallery close to Sloane Square in London’s Chelsea. Specialising in modern craft, the shop was a cosmopolitan trove where visitors could find Mexican rugs, Japanese ceramics and Welsh quilts.

Rose, who often placed her printing blocks alongside the fabrics she made so that clients could comprehend the creative process, displayed her cloths with the respect accorded to fine art. Certainly, the fabrics of Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher merited such treatment. At Temple Place, we see lengths of their cottons handprinted with blocks, organic patterns repeating across the surface. Their austere simplicity rivals that of any 1960s minimalist painter.

Barron and Larcher were trailblazers. Barron taught herself to make vegetable dyes from traditional sources she found in British libraries, while Larcher lived and taught in Kolkata, where she observed Indian printing and dyeing techniques. The pair revived English block printing between the wars so successfully that their clients included the Duke of Westminster and Coco Chanel.

Enid Marx, who was apprenticed to Barron and Larcher, inherited their flair. Trained at the Central School of Art and Design and the Royal College of Art, her knowledge of painting and wood engraving brought rigour and nuance to her patterns. Here, a chaise-longue upholstered in grey and cream velvet bears a rhythmic pattern of tiny stars scattered between rows of bolder, abstract shapes.

Marx, and her life partner Margaret Lambert, who were also keen collectors of popular art, left their personal collection to Compton Verney in Warwickshire. Surrounded by parkland designed by Capability Brown, it’s surely the perfect setting for Marx’s stylish, bohemian aesthetic.

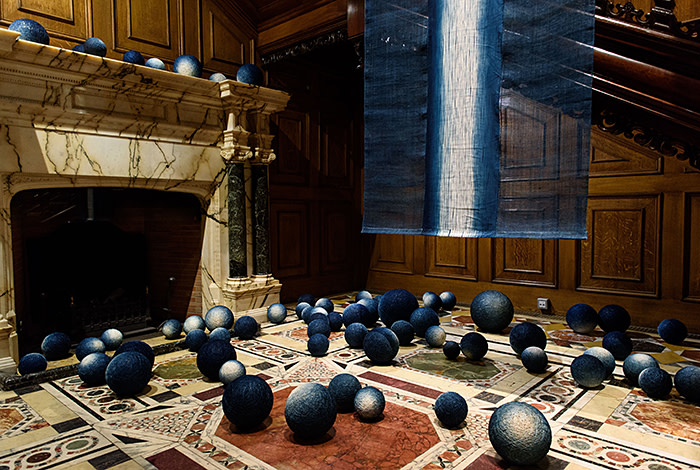

The final section of Unbound is devoted to contemporary collectors and curators Jennifer Harris and Nima Poovaya-Smith. It’s a somewhat bumpy transition from the serene, modernist chords of early 20th-century makers into expressions made some half a century later. Nevertheless, there are some glorious works here. From Manchester’s Whitworth Museum, where Harris presided as curator of textiles from 1982 to 2016, we have “Guardian” (2006), a stunning wall hanging whose pattern, part grid, part mosaic, is the result of both handloom weaving and computer-aided design on silk, palm fibre and Andean wool. Created by the Venezuelan duo Eduardo Portillo and Maria Eugenia Davila, its past-meets-present origins result in a rippling waterfall of silvery blues and creamy golds whose vitality could never have been expressed by paint. Having travelled to Asia to learn the processes involved in creating blue dyes, Portillo and Davila grow their indigo plants in Venezuela — a fine example of the cultural cross-pollinations that occur in the world of textile and cloth.

Other crosswinds blow through the display devoted to Nima Poovaya-Smith, who was curator at the Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in Bradford from 1985 to 1998 before going on to hold other significant curatorial roles. Thanks to Poovaya-Smith, not only did Bradford’s holding grow from a few dozen pieces to nearly 2,000 in total, but it developed into one of the most significant collections of contemporary art in the UK by artists from south Asian, African and Caribbean heritages.

Here, a selection of works include Sarbjit Natt’s 1996 sari, a sumptuous swath of gold “tissue” silk whose intricate geometrical pattern is, in part, hand-painted. Apparently, Natt’s inspirations include “phulkaris”, hand-embroidered textiles from Punjab, a beautiful early 20th-century example of which — covered in figures and animals in rich terracotta, gold and fuchsia — is also on loan from Bradford.

Taking curators and collectors, rather than artworks, as its starting point, Unbound weaves a cornucopia of delicate, fruitful exchanges.

twotempleplace.org, to April 19

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our culture podcast, Culture Call, where editors Gris and Lilah dig into the trends shaping life in the 2020s, interview the people breaking new ground and bring you behind the scenes of FT Life & Arts journalism. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Comments