The God Almighty Lloyd Joneses

Georgia Lloyd Jones Snoke | Jul 18, 2018

Georgia Lloyd Jones Snoke is the great-granddaughter of Frank Lloyd Wright’s uncle, the Reverend Jenkin Lloyd Jones. As her family continues to look to their roots with pride, Snoke shares the Lloyd Jones perspective on the young, gifted boy from rural Wisconsin who became America’s greatest architect.

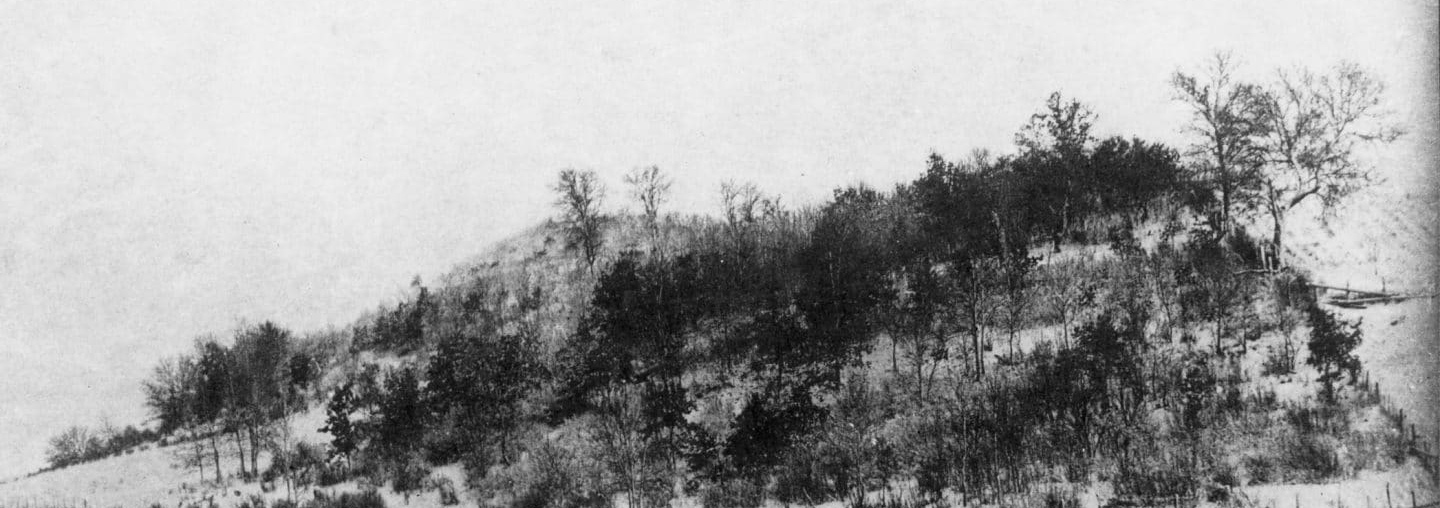

PHOTO, ABOVE Frank Lloyd Wright, photographer. Jones Valley, Looking Northwest from near Current Intersection of Routes 23 and T. ca. 1900. Collotype. PHOTO, HEADER IMAGE Frank Lloyd Wright, photographer. Whittier Hill near Hillside Home School. ca. 1900. Collotype.

This article originally appeared in, “Plan,” the Spring 2017 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly.

In our ancestral home of “Y Smotyn Du” (the “Black Spot” of Wales—named for its religious unorthodoxy), the Lloyds and the Joneses are, in hushed tones, linked with the revered name of Frank Lloyd Wright.

It is only fair, then, that the Frank Lloyd Wright whom we celebrate be linked, in turn, with the Welsh Lloyd Joneses who came to Wisconsin.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s grandparents emigrated from Wales in 1844 with seven children. They sought living wages and a free religion in the longed-for promised land of America. They knew when they left Wales that all that was familiar was forever behind them, as they risked death at sea from a broken mast, and lost a child to typhoid en route to Wisconsin. They had nothing but determination, energy, drive, and prayer to get them through that first Wisconsin winter. But survive they did. And, in time, thrive.

The “Lloyd” in their name came from the erudite Welsh grandmother Margaret Lloyd. The “Jones” from her husband, John (Jones) Enoch. Once in a Wisconsin already awash with Welsh Joneses, the two names were combined to set the clan apart from all others. And it was as a clan apart that the family grew. And it was that clan that helped form a young, gifted, iconoclastic nephew.

By the time Frank Lloyd Wright was an adolescent, his aunts and uncles had settled in a glorious green valley near Spring Green, Wisconsin, and built a small family chapel there. Five had farms, one became a preacher in Chicago, and two sisters developed the extraordinary Hillside Home School for the children of their siblings. Ultimately, the school became famous far beyond the Valley, the preacher became famous far beyond the region, and the farmers proved to be innovative, creative, curious, daring, outspoken—sought as trustees for the University of Wisconsin, and leaders in local government. These were the aunts and uncles Frank knew—and more than once feared.

By this time his parents had divorced and his formidable mother, Anna, had turned to her farmer brothers in the Valley to give her son some summer work. How he hated it is well-known. He wrote of running away, of being dragged back to his Uncle James’ home, of seething with anger, of feeling trapped. But there before him was “the Valley” in all its beauty. It was his solace in his solitary moments. He learned to “add tired to tired and then add tired,” while developing a deep, abiding, transformative love for this Valley. Despite his inclinations, he learned to work. To work hard. He had no choice.

The family was close—it could also be contrary. There were outspoken arguments countered by tearful Welsh hymns. The school was near at hand to encourage education and introspection. Uncles experimented with stocking ponds with trout, breeding rare cattle, rotating crops, inventing new ways of doing, observing, trying (and occasionally) failing. Everyone contributed to the school in some way, and when the school needed a windmill, the school teacher aunts chose Frank to build it. The uncles were aghast. It would fall in the next storm.

But the aunts trusted Frank. The windmill, “Romeo and Juliet,” still stands, as does the “stone school building” he built for them in 1902 – 03 and that he later incorporated into what is now known as the School of Architecture at Taliesin. The Valley nurtured Frank. And Frank, in turn, beautified the Valley.

After an eventful, bursting lifetime, Frank Lloyd Wright was buried in the small family chapel where, as a teenaged “boy architect belonging to the family,” he had “looked after its interior.” While his bones no longer lie there, the ground where he once lay is hallowed, along with the burial sites of grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins. His Lloyd Jones roots were strong, bored into his very being. That they blossomed into massive creativity, acerbity, willfulness, and determination is just one of the many God-given gifts that contributed to his genius.

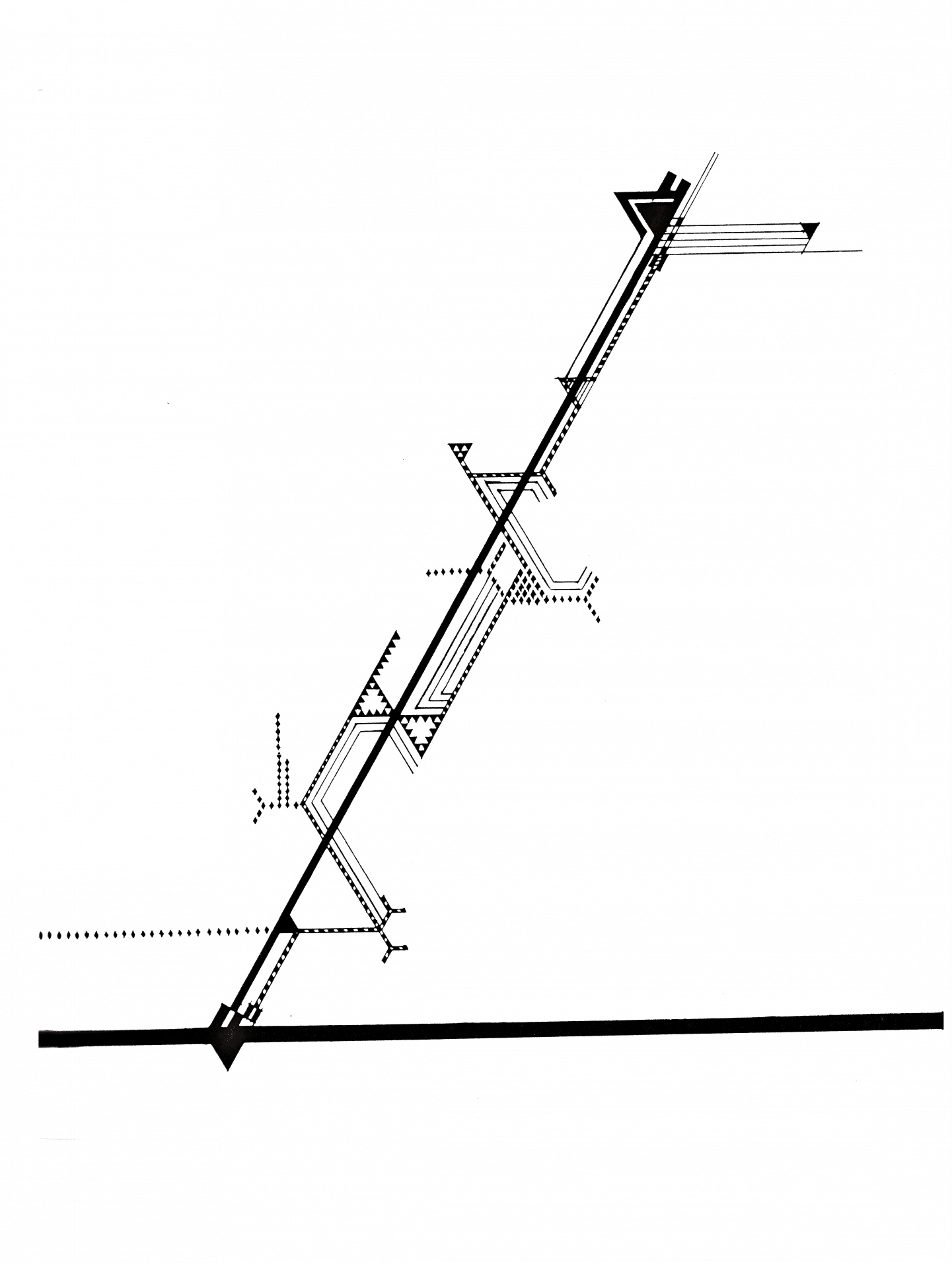

An abstraction by Frank Lloyd Wright from Book One of his autobiography, titled “Family—Fellowship,” in which he discusses his childhood.

about the author

Georgia Lloyd Jones Snoke comes from a newspaper family. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Scripps College in Claremont, California, received an MA in TV and Film Writing and Production from Loyola of Los Angeles, and worked as a TV newswoman in Tulsa. As first a dancer, then a teacher, then a cameo performer, she has worked extensively with Tulsa Ballet. Her other passion is the Lloyd Jones family’s Unity Chapel near Taliesin where she has served as historian, board member, and president.